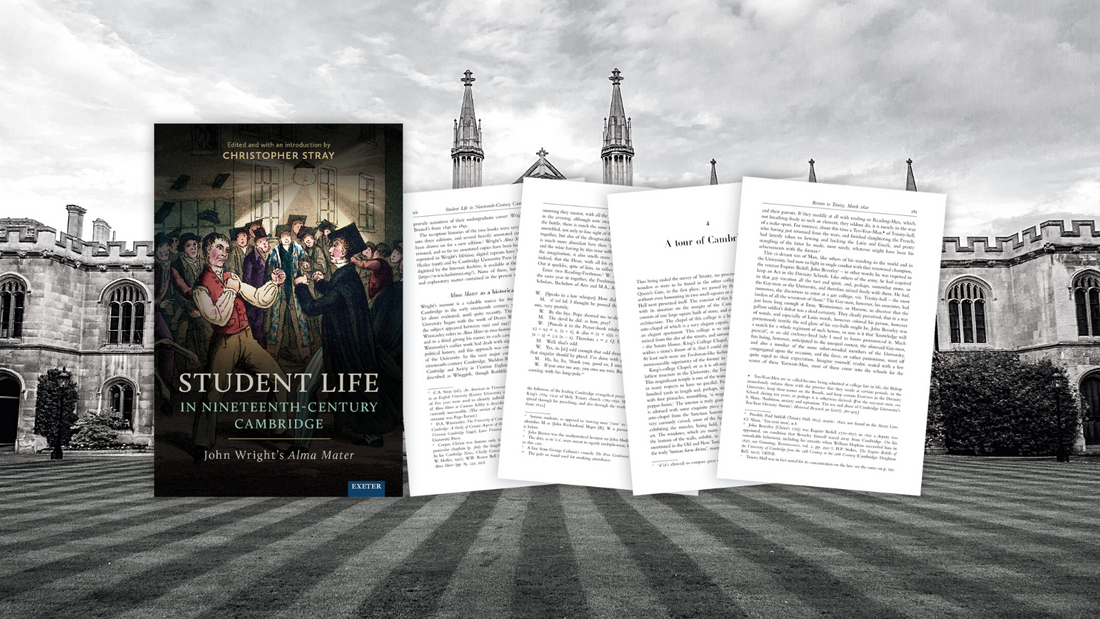

Christopher Stray talks to us about Student Life in Nineteenth-Century Cambridge: John Wright's Alma Mater.

When did you first learn of John Wright and what piqued your interest in his memoir?

I came across references to him, his maths books and his memoir in the literature on Cambridge mathematics, for example Andy Warwick’s Masters of Theory: Cambridge and the Rise of Mathematical Physics (2003). It struck me that the man and his memoir had not been investigated in their own right. After about 1836 he stopped publishing and disappeared from public view. Charles Bristed’s Cambridge memoir Five Years in an English University (1852), on the other hand, was reprinted several times into the 1870s. (A new edition of his memoir was published by the University of Exeter Press in 2008.)

Student Life contains contextual and biographical information beyond Wright's original text. How did you approach the research for the book?

In the usual way: checking on information sources like university and college records and private correspondence, reviews and so on. Only one letter by Wright has been found. Two reviews of his book were published, probably by the same person. There is little information on his family and on his birth and baptism records. I had a lot of help from historians of mathematics who knew his books and were curious to know more about their author.

‘The Battle of Peas Hill’ from ‘A Brace of Cantabs’,Gradus ad Cantabrigiam:or, New University Guide to the Academical Customs, and Colloquial or Cant Terms peculiarto the University of Cambridge; Observing Wherein it Differs from Oxford(London: J. Hearne, 1824)

Of the information that came to light during your research, what surprised you the most?

The story of his chequered career and personal history: marriage, children, his wife’s adultery and their children’s being sent to a workhouse, spells in debtors’ prisons. And most of all, his taking to crime, conviction and transportation to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Here there is an extensive literature, including Charles Bateson’s The Convict Ships 1787-1868 (1959), and extensive archival records available through the Tasmanian library service.

This is the second student memoir you have edited (the first being An American in Victorian Cambridge), what is it that draws you to accounts of this type?

Tracing the lives of individuals makes for vivid accounts of student lives, institutional histories and curricula as actually experienced. Bristed was American and wrote for his countrymen, so explained a lot of things that a British author would not have explained. Wright was a poor student who became a hack author, so told a story that would have been unfamiliar to many readers. His book reads in parts like a picaresque novel. He is often unreliable – for example, he gives the wrong dating for his admission to Trinity College – but usually provides a lot of interesting detail.

The Hall of Trinity College. W. Combe, A History of the University of Cambridge: Its Colleges, Halls, and Public Buildings (London: R. Ackermann, 1815)

What parallels would present day students draw from Wright's experiences?

The fragility of his finances might remind them of their own situation, with loans instead of grants and increasingly expensive rents. With any luck Wright’s history of marital breakdown, imprisonment for debt and transportation for larceny would not chime with their own experience.

Who is the target audience for the book and what do you hope readers will take away from Student Life?

The main target audience is historians of universities, especially Cambridge, and of mathematics and publishing. But Wright’s memoir is engaging and vividly written, so could also appeal to a wider audience who want to know about the man and his experiences and not just about the history of institutions and curricula. Wright also tells us a lot about the social history of universities: town vs. gown conflicts, drinking, sport and the use of prostitutes.

Learn more about Student Life in Nineteenth-Century Cambridge and order your copy here.